Main ContentCurrent Exhumations

In 2019, the Mississippi Legislature passed legislation that allows UMMC to proceed with exhumation and relocation of the remains on the UMMC campus. In 2021, the Legislature allocated $3.7 million in funding to go toward exhuming the remains of those interred in the cemetery.

The Summer 2025 Asylum Hill Field School - Applications now closed

Check back later in 2025 for information about the Summer 2026 Asylum Hill Field School.

Archaeological Crew

Dr. Jennifer Mack, Lead Bioarchaeologist

Dr. Jennifer Mack, a native of Pensacola, Florida, is the Lead Bioarchaeologist of UMMC's Asylum Hill Project. After completing a BA at Emory University, she spent several years working for private archaeology firms and state agencies, and she received osteological training at the University of West Florida before obtaining a PhD from the University of Exeter. She has been published in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology and has co-authored two books, Dubuque's Forgotten Cemetery: Excavating a Nineteenth-century Burial Ground in a Twenty-first-century City (University of Iowa Press, 2015) and In Praise of Small Things: Death and Life at the Late Neolithic-Early Bronze Age Burial of Bolores, Portugal (British Archaeological Reports International Series, 2015). Dubuque's Forgotten Cemetery was selected for the James Deetz book award by the Society for Historical Archaeology in 2017.

Dr. Mack has a particular interest in institutional cemeteries and the diverse populations represented within their grounds. Past research projects include the Volusia County Poor Farm Graveyard in Florida and the Johnson County Poor Farm and Asylum Cemetery in Iowa.

Gabby Lofland, Crew Chief

Gabrielle Lofland is originally from Delaware but spent most of her childhood in Albania and the surrounding Balkan countries, immersed in their rich history and burgeoning archaeology, which sparked her own interest in the discipline. Upon returning to the U.S., she earned a BA in English literature and then later a BA in anthropology at UWF in Pensacola, FL with a focus in forensics and archaeology. She has spent the last year working as a CRM field tech, primarily in the southeast, gaining experience in various excavation methods. Now, she is honored to partner with UMMC and bring her academic interests and experience as a field technician to the Asylum Hill Project.

Emily Wicke, Field Technician

Emily grew up in Pensacola, FL. Since 2002, she has worked as an archaeological field technician, gathering data for Cultural Resource Management reports from forests all over North America. She has an adjacent interest in various arts and crafts. She makes drawings/paintings with mixed media and has a daily practice of textile production, which includes spinning fiber, dyeing yarn, knitting, and weaving on historic counterbalance looms. She enjoys a regular trail-running habit to help clear the mind.

Stacia Yoakam, Field Techinician

Stacia received her MA in Archaeology from the University of Sheffield in England and received her BS in Anthropological Sciences and BA in Classics from Ohio State University. Trained in bioarchaeological analysis and osteology, she has worked with populations both ancient and historic, ranging from Roman Citizens to 1950s Americans. Most recently, she worked as a cultural research management specialist focusing on the removal, study, and re-interment of cemeteries impacted by modern construction. Her interests lay primarily in paleopathological analysis and osteobiographical reconstruction. She looks forward to working with the descendant population and the people of Jackson, Mississippi, to help remember and tell the stories of the people interred in the Asylum Hill Cemetery.

Jordan Wilson, Field Technician

Jordan Wilson is originally from Vicksburg, Mississippi, where he developed a lifelong interest of history and cultural studies. He received a BA in History and Anthropology from Northwestern State University in Natchitoches, Louisiana, in 2015, where he worked for the Cultural Resource Office and Williamson Museum. Currently, he is enrolled in an MS in Geographic Information Sciences program at Northwestern Missouri State University. He has worked in a number of roles within the field of cultural resources over the years, including Cultural Resource Manager for the Louisiana Army National Guard where he picked up an interest in various environmental conservation disciplines and the interdisciplinary approaches to them. Jordan also does work as a cemetery conservator for historic cemeteries. His research interests include the pre-contact southeastern United States, zooarchaeology, and cemeteries, both above and below ground.

Bryce Sermons, Field Technician

Bryce Sermons is originally from Georgia and received his BA in Anthropology from Georgia Southern University in 2022. Since 2022, he has worked as an archaeological field technician across the southeastern U.S. as well as in California and Iowa. During this time, he gained experience in all phases of archaeological excavation across historic, precontact, and mortuary contexts.

Katherine Dunning, Field Technician

Katherine grew up in Bloomington, Indiana, and completed bachelor's degrees in History and English Literature at Indiana University. She moved with her fiancé to Florida in 2015 and was accepted into the Applied Anthropology master's program at the University of South Florida. There, she was trained in bioarchaeology and osteology, and researched isotopic and biomolecular analysis methods for bioarchaeological materials. Her thesis focused on the isotopic profiles of bubonic plague victims buried on the quarantine islands of Venice, Italy. She additionally completed a graduate certificate in bioinformatics, applying it to her work in proteomic analyses of bioarchaeological samples. Prior to joining the Asylum Hill Project, she worked in CRM, gaining experience with the different phases of archaeological work and historical cemetery excavation. She is delighted to now be a part of the Asylum Hill Project and the important work being done at this site.

Marla Wankowski, Field Technician

Marla is a Northwest Florida native, growing up in Fort Walton Beach and earning her BA in Anthropology, specializing in Maritime Studies at the University of West Florida in Pensacola. Since finishing her degree in 2016, she has worked as an archaeological field tech, crew chief, and archaeological monitor in various states across the U.S., including Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, Louisiana, North Carolina, Virginia, Tennessee, Missouri, Oklahoma, Texas, and California. She has used this time to gain a broader understanding of archaeology across the U.S. while working on a variety of projects, including a large solar energy project in California, where she worked closely with Native American tribal representatives to ensure that their heritage and archaeological sites were treated with care and respect. During her time in Virginia, she discovered a passion for outreach and education in archaeology while working with local museums and non-profit organizations.

IN MEMORIAM

Dustin Clarke, Former Archaeological Crew Chief Tragically, Dustin Clarke passed away suddenly on August 28, 2023, from a heart-related event. He is sorely missed by his family and the Asylum Hill Project crew. The contributions Dustin made in establishing the project are inestimable. |

RECENT PRESS

Progress mounts on Asylum Hill

Published on Monday, October 3, 2022

By:Gary Pettus, gpettus@umc.edu

In a milestone for the years-long Asylum Hill Project, a team of archaeologists should begin exhuming human remains this month on the campus of the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

Clearing the way for this next step of the undertaking was last month's removal of trees on a section of land holding the graves of thousands of people who were residents of the vanished State Hospital for the Insane, which operated for 80 years on what is now Medical Center ground.

The cutting of trees over an approximately four-acre section of the project area was a major phase of the ongoing mission to unearth, study and respectfully memorialize those asylum patients whose bodies were never claimed as UMMC officials map out an ethical way to reclaim the burial site for potential land development.

About to commence as well is the construction of a six-foot high, chain-link privacy fence with slats to obstruct views outside the excavation site in the northeast corner of the campus.

Didlake

Didlake"Right now, the focus is on getting the equipment here, the excavation team here, getting a fence up and excavating the remains," said Dr. Ralph Didlake, leader of the Asylum Hill Project and director of the Center for Bioethics and Medical Humanities.

That equipment includes a track hoe, which has a digging arm. Its operator will carefully scrape away the top layer of soil over the burial ground, just inches at a time, until the soil's appearance changes, indicating the presence of interments beneath.

Mack

Mack"The contractor, who is from Mississippi, specializes in this type of archaeological machine excavation," said Dr. Jennifer Mack, lead bioarchaeologist for the undertaking.

A team of seven archaeologists, including Mack and scholars drawn from locations such as New York, Florida, Ohio and even Guam, some 7,500 miles away, will do the rest by shovel and hand.

"I'm hopeful we'll start excavating by the end of October," Mack said.

Tree removal was necessary before exhumations can begin. Most of those taken down were hardwoods, Didlake said. "We think there are only a few trees that date back to when this area was an active cemetery."

The project includes plans for tree replanting. The types of replacement trees will be based on the inventory documented by Lida Gibson, the assessment and research coordinator for Asylum Hill. "We do want to re-establish the tree canopy on campus," Didlake said.

But, Mack said, "obviously not in the same place."

As work proceeds, the experts cannot be sure how deep the graves lie. Thanks to geophysical surveys and other means, they have been able to estimate that as many as 7,000 constitute the asylum cemetery. The first coffin, discovered in late 2012, was about one foot deep.

Mack estimates that the ones about to be uncovered will be four or five feet down.

A harvesting machine known as a feller buncher takes down a hardwood during the tree removal phase of the Asylum Hill Project. The project includes plans for tree replanting to re-establish the tree canopy on campus.

The area archaeologists will concentrate on first stretches along University Drive, from East University Drive along Lakeland Drive, near the St. Dominic Hospital's property line.

"The project will work its way southward toward Central University Drive," Didlake said.

Originally named the Mississippi State Lunatic Asylum, the institution served about 30,000 patients between 1855 and 1935. The thousands of residents who died were buried with wooden markers, which deteriorated and disappeared over time.

A list of asylum patients who were buried in the cemetery between 1912 and 1935 is available; but, without markers, no one knows exactly where each one lies.

In July, Mack and Gibson held a virtual seminar to inform UMMC employees about the archaeological work funded, so far, by $3.7 million from the State Legislature. In addressing some misconceptions, they said:

- There is no reason to think that the asylum dead were buried in mass graves. Ground-penetrating radar and other means have revealed the presence of individual grave shafts.

- There is no risk of biohazard contamination.

- The graves will not be bulldozed.

Removal of trees on a section of the UMMC campus has been necessary so excavations can proceed in the Asylum Hill Project.

"As we excavate, we are also looking at coffin materials, personal items such as buttons and pins," Mack said during the presentation. "They will be documented; each item could potentially help narrow down a burial date, and could therefore help with identification." Archaeologists will also record the size and location of each grave.

They will gather osteo-biographical sketches as well: age, sex, ancestry, height, past illness, trauma, etc. Such details can help whittle down the list of candidates for potential identification.

"This will allow is to tell a person's story," Mack said. "Even if no name is found, we can rescue the individual from the anonymity imposed by the grave."

Descendants of asylum residents frequently ask about the possibility of identification through DNA. DNA analysis is sometimes impossible because of degradation, Mack said. "That's why we will focus on presumptive identification.

"We are having conversations with DNA specialists who are interested in helping us identify individuals, if possible, and returning them to their families."

Gibson has been in contact with about 150 descendants of patients. They have been kept abreast of Asylum Hill's progress and have been invited to participate in virtual question-and-answer sessions about the excavations and to contribute oral histories and other information.

Gibson

GibsonMany of the patients committed in the past may not have had a mental illness, Gibson said. "What was considered mental illness then is not always considered mental illness today. Some of those conditions are treatable now." In fact, she said, some physical ailments, such as pellagra and epilepsy, could lead to "neuro-psychiatric manifestations."

Why would a family not claim a body? Transportation and communication were issues, Mack said. Documentation shows that hospital officials tried to contact families, but there was no refrigeration then. So, they were buried, if not claimed, within 24 hours. They had to be interred on site, she said.

So far, 66 graves have been excavated – those uncovered after construction crew discovered a single pine coffin a decade ago. Archaeologists at Mississippi State University analyzed those remains.

It may take five to seven years to disinter and analyze the remaining thousands and accomplish other aims. Another goal, when funding becomes available, is to create a memorial and laboratory that will serve as a permanent resting place for those who could not be positively identified and returned to their families for reburial.

An archaeological field school for interested college students may also be in the works for next summer. UMMC students have already contributed their labor; among them are two medical students, Ruth Brooks and Katie Weeks, who volunteered to transcribe asylum records, such as yearly reports to state legislators.

"They've done an amazing job. We always welcome students to the project," Gibson said.

Hospital records are held by the Mississippi State Department of Archives and History, one of Asylum Hill's many stakeholders. Others include Native Americans. "We are exploring the possibility that Native American graves are present, as we work with the MDAH and the Choctaw Nations," Mack said.

Those buried represent every county in the state; at least half are African Americans, Mack said.

"We continue to work with a community advisory board, answering people's questions about their ancestors. This process truly serves the people all over Mississippi."

Their markers didn't last, but their stories will, says new Asylum Hill scholar

Dr. Jennifer Mack visits the UMMC Cemetery, located in the northeast corner of the campus, where human remains were reburied after being discovered on Medical Center land in 1992. Markers seen here were removed from Asylum Hill in the 1970's. For the next phase of the Asylum Hill Project, Mack will be working with human remains whose markers have disappeared.

Dr. Jennifer Mack visits the UMMC Cemetery, located in the northeast corner of the campus, where human remains were reburied after being discovered on Medical Center land in 1992. Markers seen here were removed from Asylum Hill in the 1970's. For the next phase of the Asylum Hill Project, Mack will be working with human remains whose markers have disappeared.Published on Monday, June 27, 2022

By:Gary Pettus, gpettus@umc.edu

News of the graves discovered several feet beneath a campus road raced more than 700 miles from Jackson to Iowa City, running smack into the aspirations of Dr. Jennifer Mack.

"I thought, ‘That thing in Mississippi – that's going to be my next big project,'" Mack said.

Now, 10 years later, it is.

In early April, Mack moved into an office at the University of Mississippi Medical Center to help breathe life into the stories of people long dead and almost forgotten and ensure that UMMC has land for future use.

As lead bioarchaeologist for the Asylum Hill Project, she has joined the effort to exhume, study and memorialize the people buried in thousands more graves uncovered since that first discovery in 2012 on Medical Center land.

"This project is larger than any I've worked on before," she said.

That's coming from someone who has been part of archaeological excavations in this country, Ireland, Germany, Serbia, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

While working for University of Iowa, Mack scrutinized human remains from a Stone Age tomb discovered in Portugal.

Just 85 miles from Iowa City, she helped excavate a large Catholic graveyard named the Third Street Cemetery, a feat that led her to describe it as co-author of "Dubuque's Forgotten Cemetery: Excavating a Nineteenth-century Burial Ground in a Twenty-first-century City." For that, the Society for Historical Archaeology presented her and colleague Robin Lilliewiththe 2017 James Deetz book award.

Gibson

Gibson"I believe she is the perfect person to work on Asylum Hill," said Lida Gibson, assessments and research coordinator for the project and a film documentarian coordinating its oral history mission.

That mission began soon after a road construction crew unearthed a decade ago the resting place for about five dozen unmarked, pine coffins. The workers had accidentally bared burial ground remains from the long-shuttered Mississippi State Insane Hospital, originally the Mississippi State Lunatic Asylum, from which the project takes its name.

Since then, UMMC officials have sought an ethical way to reclaim the burial site for potential land development. That means navigating a path that serves patients in the Medical Center's future, who deserve the services of a campus allowed to improve and expand; and patients from the past, former asylum residents, who merit respect.

"We need someone with Jennifer Mack's experience excavating human remains at historic cemeteries," Gibson said. "Someone who knows the protocols and the respectful nature that goes into exhuming these individuals."

As for returning those individuals who can be positively identified to families for reburial, project leaders are working with known descendants to resolve legal and practical issues, Gibson said. Otherwise, a planned memorial/lab will serve as a "permanent resting place."

As a bioarchaeology project, "it is one of the largest, if not the largest, ever undertaken in the United States," said Dr. George Bey III, a member of the Asylum Hill Research Consortium serving as education coordinator, helping develop a multi-year field school program for budding archaeologists.

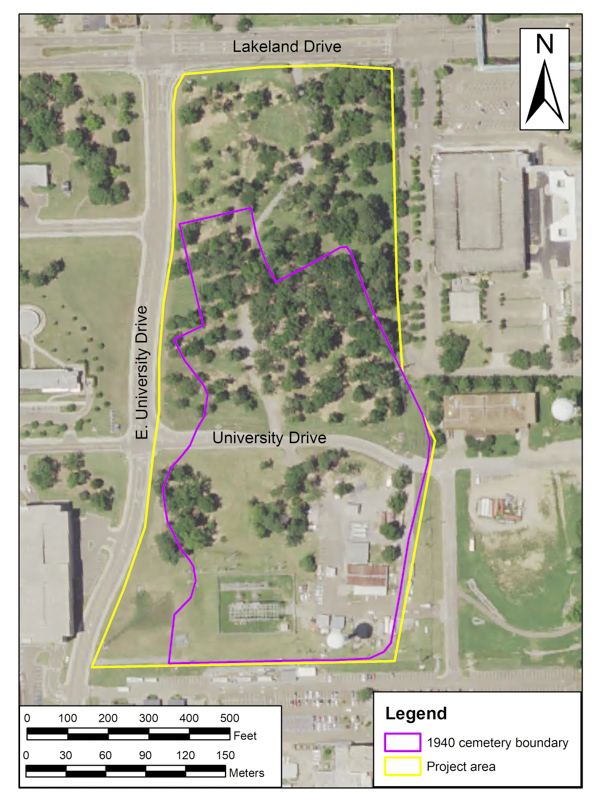

A modern aerial photograph of the northeast corner of UMMC's campus shows the archaeological project area boundary superimposed in yellow. The purple outline indicates the approximate location and extent of the Asylum Hill Cemetery, as viewed in an aerial photograph from 1940.

A modern aerial photograph of the northeast corner of UMMC's campus shows the archaeological project area boundary superimposed in yellow. The purple outline indicates the approximate location and extent of the Asylum Hill Cemetery, as viewed in an aerial photograph from 1940."Dr. Mack has directed large-scale burial excavations and knows how to get the remains out of the ground, properly curated and treated," said Bey, professor of anthropology and Chisholm Foundation Chair in Arts and Sciences at Millsaps College in Jackson.

"She also has worked with communities to make sure the human remains were treated ethically and the descendant communities are respected. She brought the experience and expertise we needed."

Mack had been waiting for an opportunity to come back South, where she had explored cemeteries as a young girl in her Florida hometown.

"In Pensacola, the Victorian cemeteries above ground were like art displays, so beautiful," Mack said. "It was fascinating to me that you could put together stories about a person's life by reading the words on these monuments."

When she was 10, her mom arranged for her to go on a real archaeological dig for a day. "It was miserably hot," Mack said. "I got blisters and we didn't find anything." This put her out of sorts with archaeology. The estrangement did not last.

During her second year of college, an art history course at Emory University put her heart a-flutter again. An internship at Historic Oakland Cemetery in Atlanta sustained the beat.

On her journey to a career in archaeology, Mack strayed from the usual course. "I started in general archaeology and forced my way in, working primarily in cultural resource management," she said. Distinguished from academic archaeology, it embraces threatened or vulnerable historical sites, protecting and managing elements of its heritage.

"As an archaeologist, though, you end up working in unmarked cemeteries," she said. "Those are the ones that tend to have construction encroach on them when people don't realize they are there."

In Dubuque, construction had, several times, disturbed the unmarked 19thcentury burial ground dedicated to the Catholic parishioners of St. Raphael's Cathedral. Eventually, the Iowa Office of the State Archaeologist moved more than 900 of the burials that remained. For five years, starting in 2008, Mack was involved in the excavation.

"Thirteen people were presumptively identified," she said. There were some clues. "They were buried in family groups," Mack said. "Also, there were some partially preserved coffin lid crosses.

"Coffin lid crosses were common decorations in Catholic burials through the late 19thcentury. And these crosses were often engraved with the name of the deceased, date of death and age at death."

But markings, decorative or otherwise, are absent for the asylum patients. "They weren't buried in unmarked graves," Mack said. "They were buried with wooden markers, but wooden markers don't last."

Those had marked, for a time, the graves of those who had not been claimed by families from an institution that operated between 1855 and 1935 on what became Medical Center property. Thousands of asylum patients died. Through modern-day geophysical surveys and other means, as many as 7,000 are estimated to lie under several acres.

Telling their stories is easier than connecting remains with names.

Mack, who earned her PhD in archaeology at England's University of Exeter, is also schooled in human osteology. Through analysis of skeletal remains, she can yield an "osteobiography": age, sex, ancestry, height, evidence of illness, evidence of trauma and activity.

"Once we have that information, as well as burial date information that can be gleaned from the materials in the graves, such as coffin nails, all of that can be compared to burial records," Mack said.

"In some cases, we can narrow down pretty well the candidate pool for the identity of the person buried in an individual grave." A DNA comparison might be possible if descendants are still around, she said.

"Even if the osteobiography doesn't narrow down the possibilities to a person with a certain name, we can still tell a story about a life – particularly with the help of descendants.

"For me, that's really the goal: to return the personhood to the individual, and remove from them this imposed anonymity."